Free monoids and free monads are important concepts to understand in functional programming. A free monoid on type A is just List[A]. List is the single most widely used data structure in functional programming and everyone knows what a list is. But not everyone knows why lists are called free monoids, and what is so “free” about it. And it pays to do so, because understanding what free monoids are about will make the concept of free monads much more comprehensible.

In this post I’d like to explain what free monoids and free monads are to functional programming beginners. I’ll try to explain them in a “free of category theory” way to make it easier for those who are not well-versed in category theory (although it won’t be 100% free). As a result, the explanation will be less formal or precise as it could be, and will be mainly based on intuition and examples. If you want to learn the rigorous definitions, a category theory book could be your best bet.

Basic knowledge of monoids, functors and monads required to follow this post.

Free Monoids

Intuition

“Free” in free monoids and free monads is generally taken to mean “structure free”, although I’d like to think of it as “free of unnecessary information loss”. In other words, a “free something” should be the “something” that preserves the most information, or the most general “something”, among all “something”s.

A monoid is a set with a binary operator (often referred to as the combine operator) and a unit element, satisfying certain laws. The set associated with monoid is called its underlying set. For example, (Int, +, 0) is a monoid, as is (Int, ×, 1) (the “Int” here represents all integers, rather than the Int type in Scala which is a finite set). The underlying set of both monoids is Int. When we talk about the most general monoid, we need to specify a particular set, as in the most general monoid for Int, the most general monoid for Boolean, etc.

Let’s focus on Int here. What is the most general monoid for integers? It turns out to be (List[Int], ++, Nil) where ++ concatenates two lists. Why? Because it is free of unnecessary information loss, where “unnecessary information loss” here means “unnecessary collapsing of lists”. We can collapse the lists in (List[Int], ++, Nil) in different ways to obtain different monoids. For example, if we add up all numbers in each list in (List[Int], ++, Nil), we get (Int, +, 0); if we multiply all numbers in each list, we get (Int, ×, 1). By contrast, (Int, +, 0) cannot be the most general monoid for Int, because once you collapse 2 + 3 + 5 to 10, the original elements, namely 2, 3 and 5, are gone.

Note that (List[Int], ++, Nil) does lose certain information, but that is necessary for satisfying monoid laws. For example, given List(2, 3, 5), you don’t know whether it is obtained from List(2, 3) ++ List(5) or List(2) ++ List(3, 5). That information is lost in the concatenation. In other words, both ((2, 3), 5) and (2, (3, 5)) are collapsed into (2, 3, 5). This information loss is necessary, because monoid law requires that the combine operator of the monoid be associative, so it must give the same result whether you first combine 2 with 3, or first combine 3 with 5.

So, this is basically the intuition of what a free monoid is, and why lists are free monoids. In summary, a free monoid is a monoid for a particular set A whose binary operator does not collapse elements unnecessarily (except as required by law), and List[A] satisfies this requirement perfectly. This is, of course, an extremely informal and imprecise description. Next let’s see a slightly more rigorous way of explaining free monoid, also known as universal construction in category theory.

Universal Construction

A free monoid for Int, denoted as FreeMonoidInt, is a monoid such

that, given any other monoid (A, ⊗, e), there is a 1-1 mapping between functions

of type Int => A and monoid homomorphisms

from FreeMonoidInt to (A, ⊗, e).

Here are some examples, assuming FreeMonoidInt is List[Int]:

Example 1. If (A, ⊗, e) = (Int, +, 0) and f = identity, then the monoid homomorphism identified by f maps every list of integers to their sum, and maps the empty list to 0.

Example 2. If (A, ⊗, e) = (Int, ×, 1) and f = identity, then the monoid homomorphism identified by f maps every list of integers to their product, and maps the empty list to 1.

Example 3. If (A, ⊗, e) = (Int, +, 0) and f is the following function, which maps every integer to either 1, 2 or 3:

def f (x: Int): Int = {

if (x == 1) 1

else if (x == 2) 2

else 3

}

Then the monoid homomorphism identified by f maps every list of integers List(x1, x2, ..., xk) to f(x1) + f(x2) + ... + f(xk), and maps the empty list to 0.

Example 4. If (A, ⊗, e) = ({1, 2, 3}, 〽, 1) where 〽 is defined as:

1 〽 x = x 〽 1 = xforx = 1, 2, 3x 〽 y = xforx = 2, 3; y = 2, 3

And f is the same function as above, then the monoid homomorphism identified by f maps every list of integers List(x1, x2, ..., xk) to f(x1) 〽 f(x2) 〽 ... 〽 f(xk), and maps the empty list to 1.

As we can see, it doesn’t matter what (A, ⊗, e) is or what f is. Given any (A, ⊗, e) and any f: Int => A, f always uniquely identifies a monoid homomorphism. Given any list of integers List(x1, x2, ..., xk), this monoid homomorphism maps the list to f(x1) ⊗ f(x2) ⊗ ... ⊗ f(xk), or e for the empty list. It is easy to verify that this is indeed a monoid homomorphism. This is only possible if the binary operator of FreeMonoidInt is free of unnecessary collapsing of elements, so that we can interpret each list of elements however we want at a later time, where “at a later time” means “after given the function f”.

It is easy to see that, by contrast, (Int, +, 0) cannot possibly be the free monoid for Int, as the + operator loses a lot of information. There are obviously much fewer monoid homomorphisms from (Int, +, 0) to (Int, ×, 1) than there are functions of type Int => Int. The vast majority of such functions, including the identity function, are not monoid homomorphisms from (Int, +, 0) to (Int, ×, 1). In fact, only a few special functions of type Int => Int are monoid homomorphisms, such as the function that maps all integers to 1.

Free Monads

Analogy to Free Monoids

Understanding free monoids makes free monads much easier to comprehend, as they are conceptually very similar. After all, a monad is a monoid, in the category of endofunctors. A regular monoid, such as (Int, +, 0), is a monoid in the category of sets. So they are both monoids in some monoidal category.

In functional programming, an endofunctor is just a functor, i.e., a type constructor that can map; a set is just a type. So, the main difference between free monoids and free monads is that free monoids are defined on top of types while free monads are defined on top of functors. In other words, a monoid has an underlying set, while a monad has an underlying functor.

Indeed, the join method of a monad is similar as the combine operator of a monoid:

combinetakes two values in the underlying set, and turn them into another value in the underlying set. Its type is(A, A) => A.jointakes two applications of the underlying functor, and turn them into a single application of the underlying functor:F[F[_]] => F[_].

Since a free monoid is a monoid that avoids unnecessary collapsing of elements in combine, we can make the analogy and say that a free monad is a monad that avoids unnecessary collapsing of functors in join, i.e., it records both original functor applications rather than collapsing them into a single functor application.

We now know that a free monoid is a list, so you may guess that a free monad is some structure similar as a list. Indeed, list allows concatenation, rather than collapsing, which is what we want for free monoid and free monad. Let’s see if we can take a list, change types to functors, and get a free monad.

A list is either a Nil or a Cons of a head and tail. In Scala a list can be defined as:

sealed trait List[A]

final case class Nil[A]() extends List[A]

final case class Cons[A](head: A, tail: List[A]) extends List[A]

Here’s how we change types to functors in the definition of List to get a free monad:

- We turn

Nilto “no functor application”, i.e., a raw typeA. - In

Cons[A](head: A, tail: List[A]), we turnhead: Ato a single functor application, e.g.,F[_] - For

tail: List[A], since the type isList[A]itself, we turn it to the free monad type.

Putting these together, here’s what we get:

sealed trait Free[F[_], A]

final case class Nil[F[_], A](a: A) extends Free[F, A]

final case class Cons[F[_], A](ffa: F[Free[F, A]]) extends Free[F, A]

This is exactly the free monad. Following conventions, we use Return and Bind instead of Nil and Cons, hence

sealed trait Free[F[_], A]

final case class Return[F[_], A](a: A) extends Free[F, A]

final case class Bind[F[_], A](ffa: F[Free[F, A]]) extends Free[F, A]

In practice, though, the free monad definition you encounter may look different from

the one above, for example, this is the (slightly simplified) definition of Free in Cats:

sealed trait Free[F[_], A]

final case class Return[F[_], A](a: A) extends Free[F, A]

final case class Suspend[F[_], A](s: F[A]) extends Free[F, A]

final case class FlatMap[F[_], A, B](s: Free[F, A], f: A => Free[F, B]) extends Free[F, B]

The advantage of this definition is that it is a monad for any type constructor F (also known as “freer monad”),

since it is basically equivalent to a free monad combined with a free functor.

On the other hand, in the previous definition, Free[F, A] is a monad only if F is a functor.

But for the purpose of this post, we’ll stick to the simpler definition of Free.

Lossless Join

As mentioned before, the join operation on a monad is comparable to the combine operator on a monoid. So, let’s draw the analogy again between free monads and free monoids in order to understand how join works for free monads. In a free monoid (List[A], ++, Nil), the combine operator (++) concatenates two List[A]s into a longer List[A]. Analogously, in a free monad Free[F, A], we would expect that the join operation should take two applications of functor F, namely Free[F, Free[F, A]], and merge them into a single “larger” application of functor F in a way that does not lose any information unnecessarily.

Unlike the free monoid case, the above sentence can be hard to understand without some visualization, so let’s do that. First, let’s take a look at the definition of join for Free[F, A]:

import cats.Functor

import cats.implicits._

def join[F[_] : Functor, A]: Free[F, Free[F, A]] => Free[F, A] = {

case Return(fa) => fa

case Bind(ffa) => Bind(ffa map join)

}

To see how this works, let’s first take a closer look at what Free[F, Free[F, A]] and Free[F, A] are.

- A

Free[F, Free[F, A]]is either aReturnthat contains a singleFree[F, A], or aBindcontaining anF[Free[F, Free[F, A]]], which is a container ofFree[F, Free[F, A]]s. So,Free[F, Free[F, A]]can be thought of as a tree where each node is aFree[F, Free[F, A]]. A node is an internal node if it is a container (inside aBind),F[Free[F, Free[F, A]]]. For each internal nodes, its children are theFree[F, Free[F, A]]s contained in the container. A node is a leaf node if it is aFree[F, A](inside aReturn). If eachFcontains a singleFree[F, Free[F, A]], then the tree degenerates into a list. - Similarly, a

Free[F, A]is also a tree: each internal node is a containerF[Free[F, A]], and each leaf node is anA.

Let’s call the tree of a Free[F, Free[F, A]] a “big tree”, and that of a Free[F, A] a “small tree”. A big tree is thus a tree where internal nodes are containers inside Bind, and leaf nodes are small trees inside Return. A small tree is a tree where internal nodes are containers inside Bind, and leaf nodes are values of A inside Return.

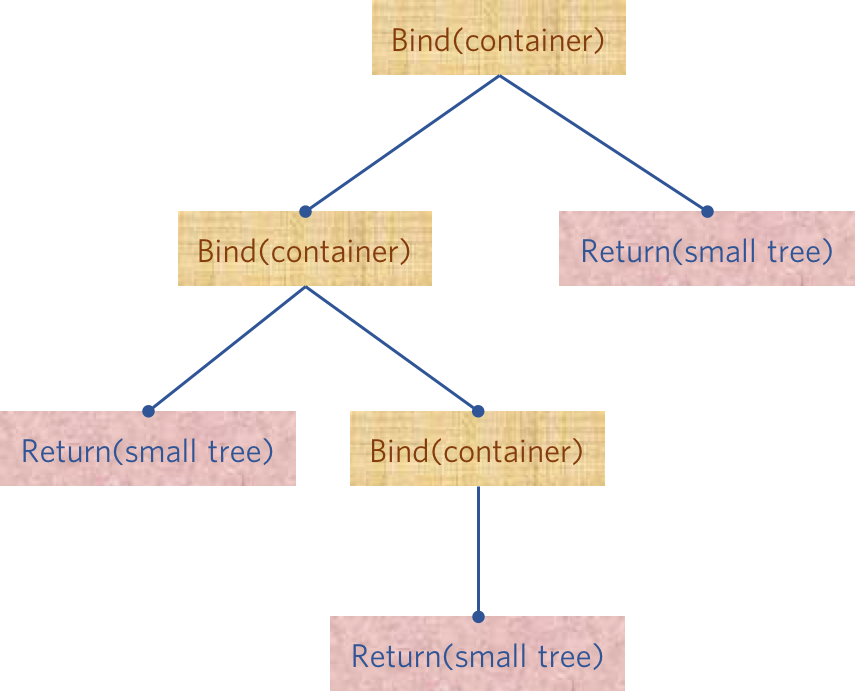

The following graph shows a big tree:

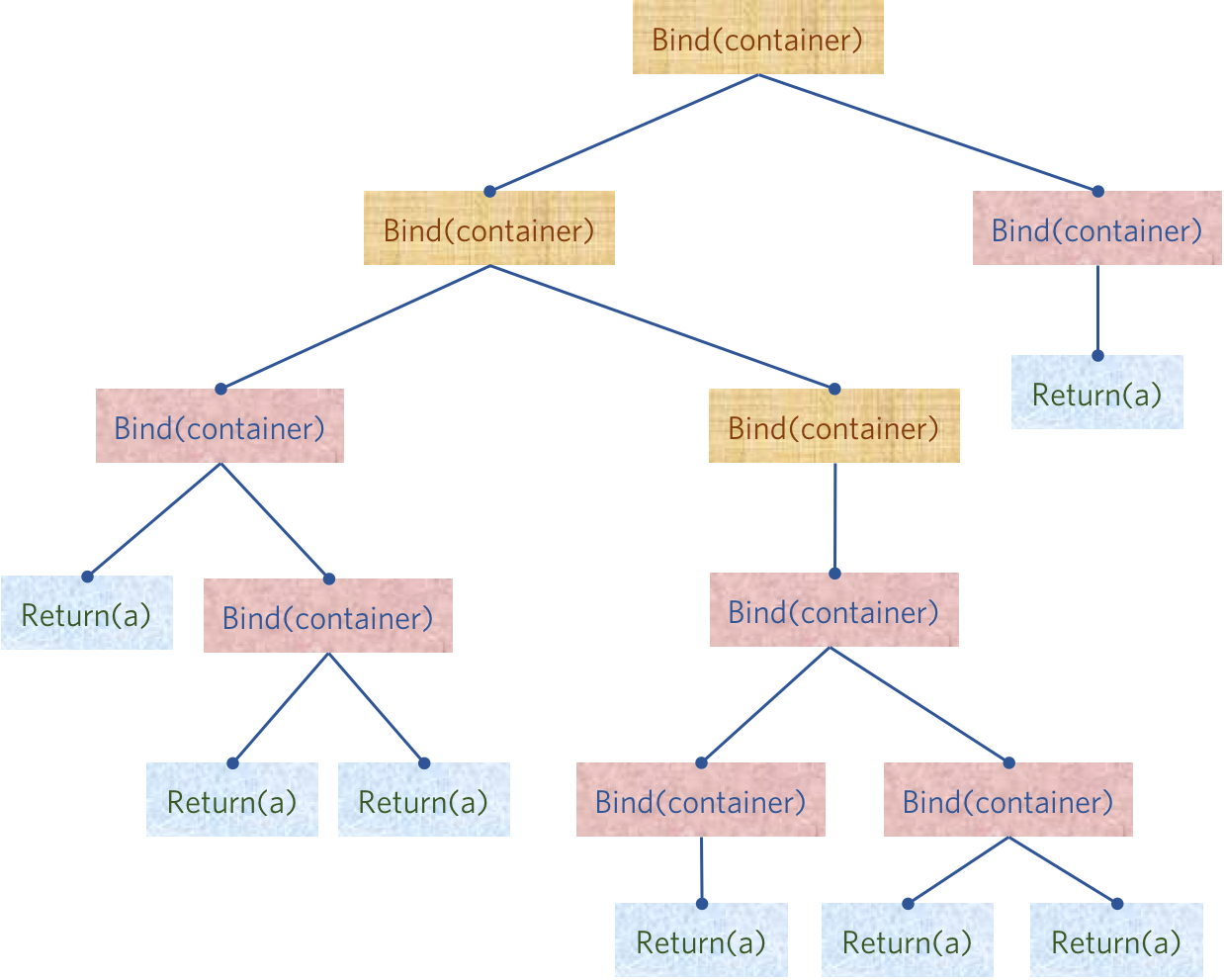

If we take the three small trees in Fig 1. out of the Returns and expand them, we may get the following tree:

As you can see, it is a small tree representing a Free[F, A], and it contains the same information as the big tree in Fig 1. No information loss. This is exactly what join does when applied to a big tree: it takes the small trees in the leaf nodes of the big tree out of the Returns and expands them, resulting in a small tree.

Free monads are widely used to encode a computation involving multiple steps as a pure value. Since the join operation of free monads are lossless (barring the necessary loss as required by monad laws), all information of the computation is preserved in a recursive structure similar as the one shown in Fig 2. This structure can be interpreted in different ways by different interpreters at a later stage.

Universal Construction

There is a universal construction for free monads which is similar to the one for

free monoids, which can be described in the following way (you can read it side-by-side

with the universal construction for free monoids to see the analogy): a free monad for

a functor F, denoted as FreeMonadF, is a monad such that, given any

other monad G, there is a 1-1 mapping between natural transformations

from F to G and monad homomorphisms from FreeMonadF to G.

In fact, the universal constructions for both free monoids and free monads are special cases of the universal construction for free objects.

Cofree Comonads

Since we’ve come this far, I’d like to briefly mention cofree comonads here. With the understanding of free monoids and free monads, it shouldn’t take a ton of work to explain cofree comonads.

In category theory and functional programming, a “co-something” is the dual of “something”, and it generally implies reversing the arrows, and turning sum types (i.e., either A or B) into product types (i.e., both A and B) and vice versa.

A comonad is obtained by reversing the arrows in pure and join in a monad:

trait Monad[F[_]] extends Functor[F] {

def pure[A](a: A): F[A]

def join[A](ffa: F[F[A]]): F[A]

}

trait Comonad[F[_]] extends Functor[F] {

def extract[A](x: F[A]): A // Dual of "pure"

def duplicate[A](fa: F[A]): F[F[A]] // Dual of "join"

}

A cofree comonad for a functor F is defined as:

final case class Cofree[F[_], A](head: A, tail: F[Cofree[F, A]])

While Free[F, A] is a sum type (it is either an A or an F[Free[F, A]]), Cofree[F, A] is a product type (it contains both an A and an F[Cofree[F, A]]).

The universal construction for cofree comonads is similar to the one for free monads, but with the arrows reversed: a cofree comonad for a functor F, denoted as CofreeComonadF, is a comonad such that, given any other comonad G, there is a 1-1 mapping between natural transformations from G to F and comonad homomorphisms from G to CofreeComonadF.

Further Reading

- A blog post on free monoids by Bartosz Milewski

- Typelevel Cats documentation on free monads and free applicatives

- A Stack Overflow question on free monads